Scientists have made a puzzling discovery to do with the Earth’s geology.

When you think of the highest peak in the world, you instantly think of Mount Everest in the Himalayas, standing at over 8,840m high.

Trekking to its summit has become the goal of many adrenaline junkies, and can be one of the most physically taxing journeys that a human can make.

But what if I were to tell you that there are mountains that exist on our great planet that are over 100 times taller?

They’re not exactly hiding in plain sight, but scientists have discovered two peaks that are continent-sized, putting mountains like Everest and K1 to shame.

Researchers from Utrecht University have found in a study that there are two colossal peaks that reach heights of around 620 miles (1,000), in what have been described as ‘islands’.

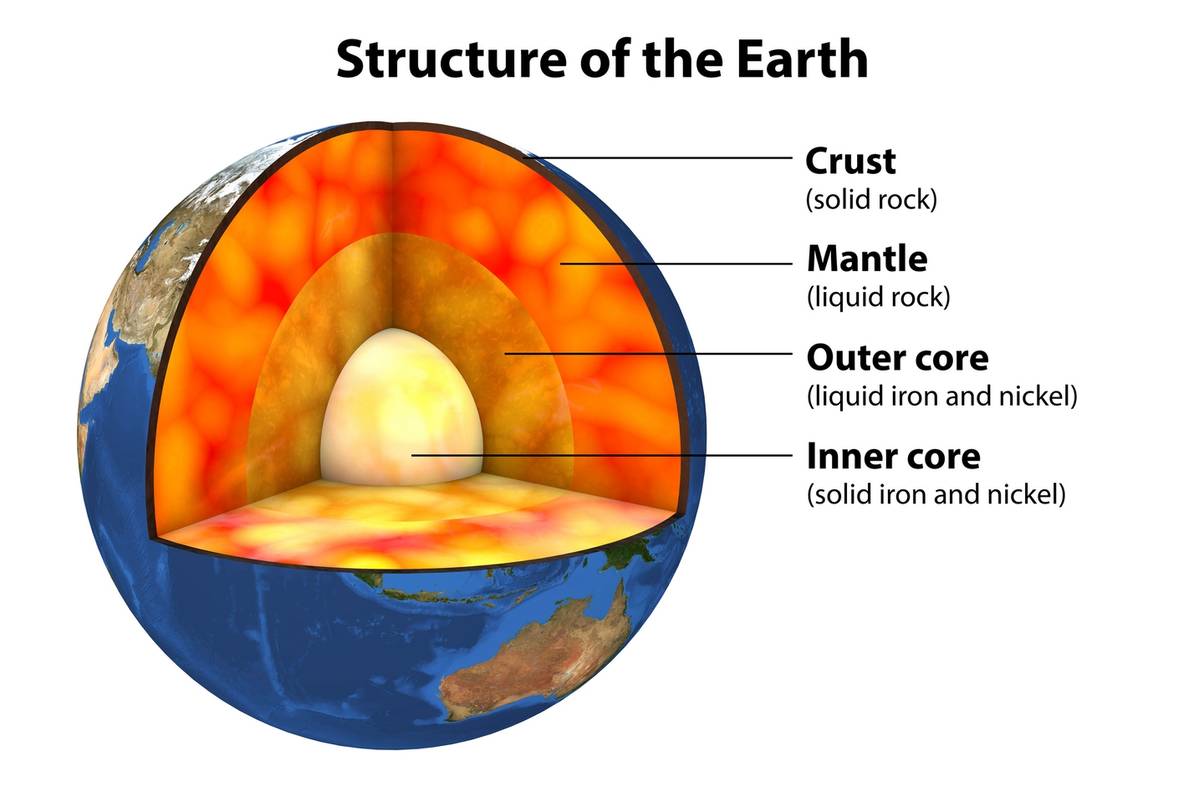

They can be found about 1,200 miles (2,000km) below the Earth’s crust, and are said to be at least half a billion years old.

It is suggested that they could be a more significant part of our history, dating back to the formation of our planet, four billion years ago.

Despite the theory that they are mountains, lead scientist Dr Arwen Deuss explained: “Nobody knows what they are, and whether they are only a temporary phenomenon, or if they have been sitting there for millions or perhaps even billions of years.”

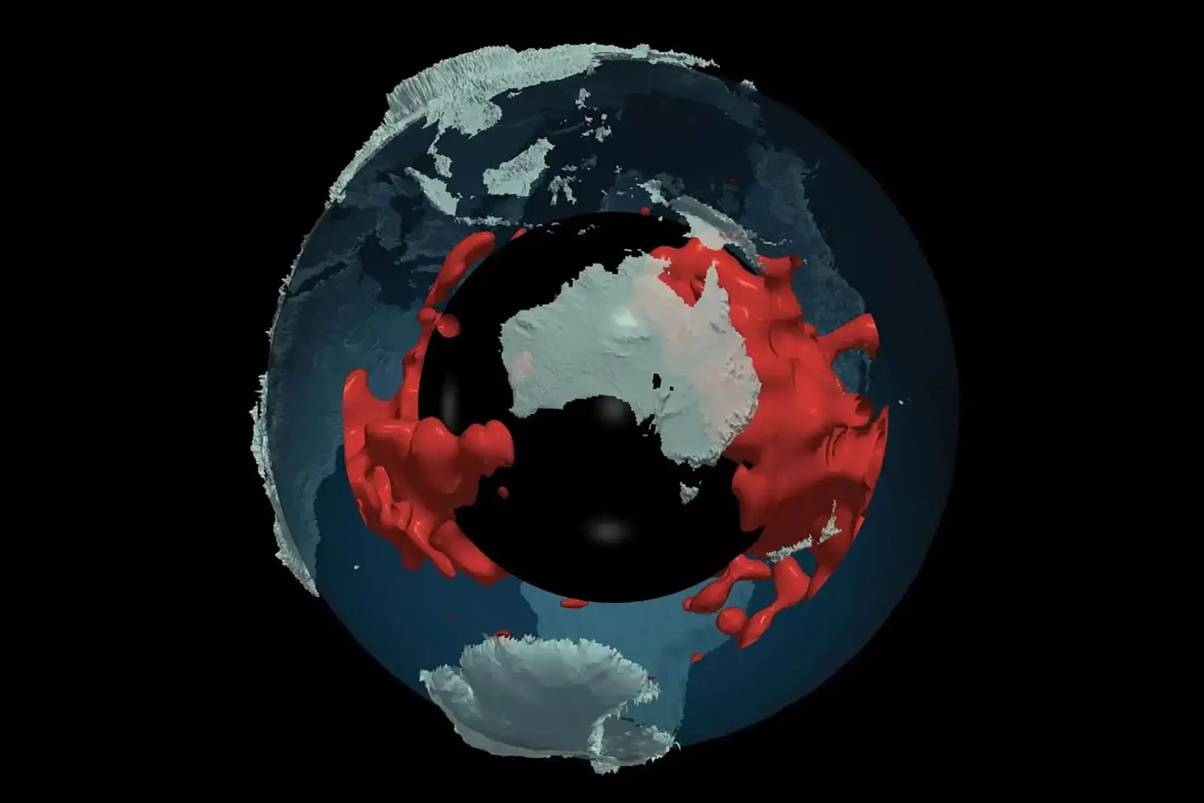

Sitting in the boundary between the Earth’s core and mantle, it can be found in the semi-solid area beneath the crust that’s under Africa and the Pacific Ocean.

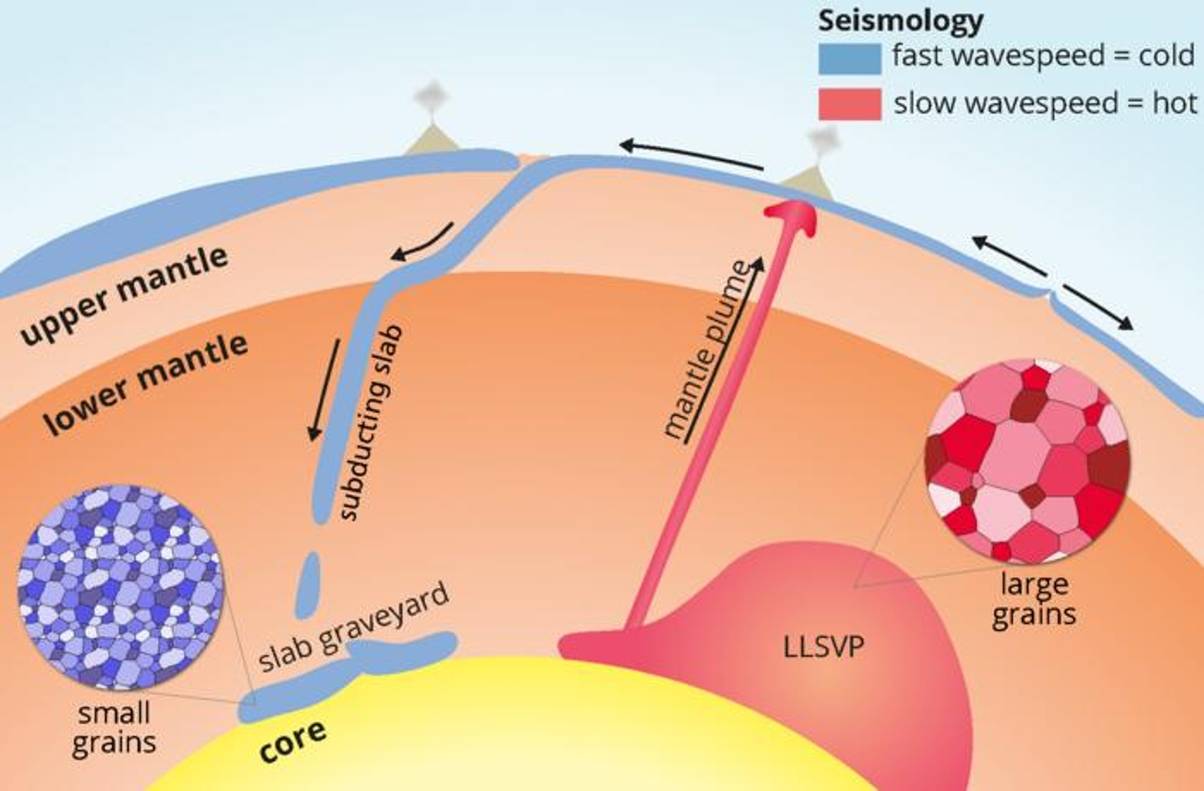

In a similar area is a number of sunken tectonic plates, that have been pushed below the surface over time in something called ‘subuction’.

The researchers further found that these islands are a lot hotter than the surrounding slabs of the Earth’s crust, and are much older – by millions of years.

Due to the effects of shockwaves from earthquakes on the planet’s interior, there are large structures that are hidden below the Earth’s mantle.

These waves are slowed and weakened when they pass through something dense or hot, so by listening to the ‘tone’ that comes out of the other side of the planet during an earthquake, scientists can map out what’s below the surface.

Studies have revealed over the years that there are two huge regions of the mantle where shockwaves slow down substantially, which have been affectionately called the Large Low Seismic Velocity Provinces (LLSVPs).

Dr Deuss explained: “The waves slow down because the LLSVPs are hot, just like you can’t run as fast in hot weather as you can when it’s colder.”

Co-researcher Dr Sujania Talavera-Soza added: “Just like when the weather is hot outside and you go for a run, you don’t only slow down but you also get more tired than when it is cold outside.”

When the tone of waves seem out of tune or quieter as they pass through LLSVPs, it is called damping.

But Dr Talavera-Soza revealed: “Against our expectations, we found little damping in the LLSVPs, which made the tones sound very loud there,

“But we did find a lot of damping in the cold slab graveyard, where the tones sounded very soft.”

The results point towards these mountains being made of larger grains that the surrounding slabs, as they don’t absorb as much energy when waves pass through.

“Those mineral grains do not grow overnight, which can only mean one thing: LLSVPs are lots and lots older than the surrounding slab graveyards,” Dr Talavera-Soza further explained.

The idea that these could be anywhere from 500 million to four billion years old goes against the belief that the mantle is constantly moving.

It was previously believed that the mantle would be mixed by these currents, but if structures – potentially billions of years old – have not been disrupted or moved by ‘mantle convection’, then it shows that it isn’t mixed at all.